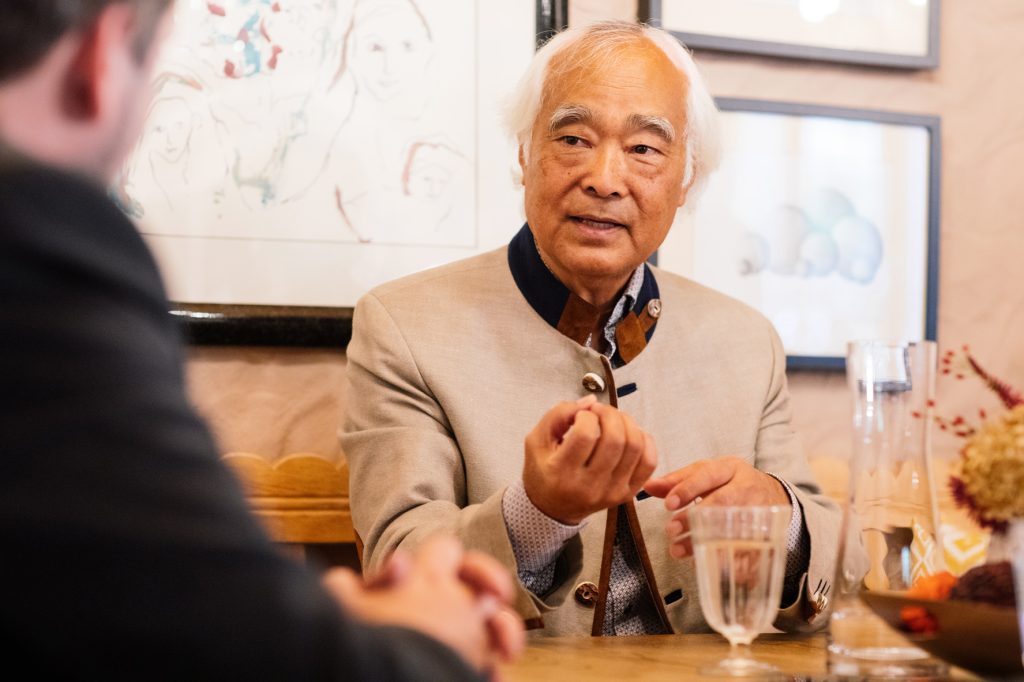

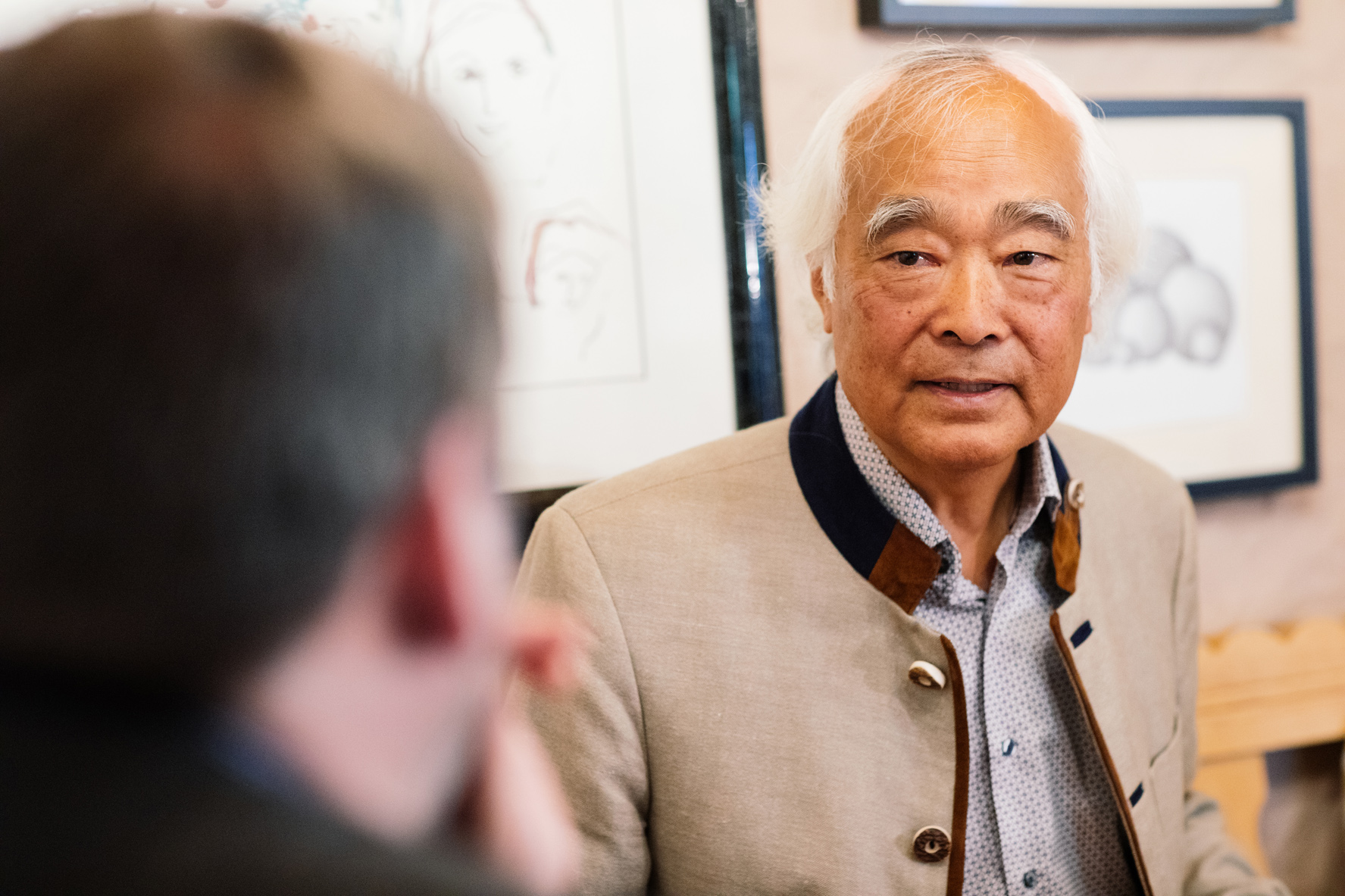

At the age of 15, Takeo Ischi, then known as Takeo Ishii, began yodeling in Japan. The hobby turned into a career that made him famous first in the German-speaking folk music world and, more recently, internationally. Now retired, he continues to yodel and has become a YouTube star, with his song “Chicken Attack” now having 25 million views on the platform. On his way from Japan to Europe, the son of a Japanese engineering entrepreneur had to overcome a number of challenges. J-BIG talked to Takeo Ischi about how the opportunity for an unusual career came about in Germany, how he feared for his work permit as a professional yodeler, how his financial situation has developed over the years and how his late breakthrough with the younger generation on YouTube came about .

J-BIG: You became known in Germany many decades ago as the “Japanese yodeler”. That’s not exactly a commonplace profession. Especially when you come from Japan! How did that happen?

Takeo Ischi: I originally wanted to study mechanical engineering so that I could take over the family business in Japan. My father was an engineer and had his own company, which made machines for drying noodles. I helped out in the business when I was young. But then I discovered yodeling for myself and pursued this hobby in Japan.

I had heard yodeling on the radio as a child, but I didn’t really know what it was. I thought there were only two kinds: the yodeling of the European Alps and the yodeling of the cowboys in country music. The most famous yodeler in Japan at that time was the American-Japanese country singer Willy Okiyama. Through my father’s colleagues, I happened to get a record of him. I liked his yodeling right away. For my middle school graduation trip to Kyoto and Nara, a classmate had compiled a small songbook. In it was the song Yama no ninki mono – the most famous yodeling song in Japan. The yodeling part of the song was nothing special, but Willy Okiyama did a really good job of performing it. That fascinated me and got me interested in yodeling.

Free Subscription

“J-BIG – Japan Business in Germany” is the e-mail magazine dedicated to Japanese companies and their business activities in the German market.

That’s why I joined the school choir in the sixth grade. I liked music and had been interested in various instruments since childhood. But I could never sing well. I always sang off-key, so I wanted to get better. A classmate yodeled a little for fun and I thought, “Ah, we Japanese can yodel too!” From then on I seriously tried to learn to yodel. I recorded a tape of Willy Okayama and tried to imitate his yodeling. At first I had great difficulty: I howled like a dog for weeks. Then I had the idea of playing the tape slowly. That way I could study exactly where the chest and head voices begin. The change between chest and head voice is the central technique of yodeling. As time went by, I could feel my yodeling improving. Through a lot of practice I was able to learn the larynx beat. I was very happy and this first success motivated me to continue.

Later I received a recording of the Bavarian yodeler Franzl Lang. It was so beautiful! From that day on, there was no stopping me. I recorded yodeling programmes on the radio and collected more records. I listened to them every day for several hours while I studied and when I went to bed. The sound of the beautiful mountains and the fresh air made me dream of actually being in the European Alps one day. That was the beginning of my enthusiasm for yodeling.

J-BIG: That was certainly an unusual hobby in Japan, wasn’t it?

Takeo Ischi: Yes, that’s right. In the beginning, I was interested in music and as singing was never my strong point, I was very happy when I could yodel a little. But I didn’t immediately turn my hobby into a career. When I was 18, I started studying mechanical engineering at Tōkai University in Tokyo. I joined the university’s hiking club, thinking that hiking in the mountains would go well with yodeling. I often used the time between my studies to look for sound patches in Tokyo. While shopping, I happened to come across a book called “Yodeling for Beginners”. When I bought the book, it turned out that the owner of the shop was an honorary member of the yodeling club in Tokyo. The club had a German name: “Alpen-Jodler Kameraden”. There was a monthly meeting where people yodeled and learned German. I immediately became a member. There were 60 of us, and many could yodel quite well. I was very shy and when I yodeled in front of everyone, my face would turn red. But with time I got used to it.

One day a German exchange student from Augsburg came to the yodel club. We became friends and she taught me German once a week. The cultural exchange made me want to travel to Europe more and more, especially to the Alps. But I was aware that a stay abroad would be very expensive. Then the German student made me an offer: “If you want to go to Germany, you can stay with my parents.” I immediately accepted. My flight left Haneda on 7 October 1973 via Moscow to Paris. From Paris, I went on to Augsburg. It was very adventurous because at that time I only knew a little German and English. When I arrived at the family home, I was told there was no room for me. I thought, “This can’t be!” But the student I had met in Japan helped me get a free room in a student flat belonging to the family of a classmate. It was a relatively large room with a shower. I was able to eat with my classmate’s family. I was worried about how I was going to pay the rent. But the family said that if I helped them with finding Japanese stamps for their collection and with tending the garden, I wouldn’t have to pay anything. I was also able to celebrate Christmas with the family. There were lots of presents and I got my first real pair of Bavarian lederhosen.

At that time I was not sure how good my yodeling was. But I soon realised that I could bring joy to others. That is why I have always enjoyed singing and yodeling. On my birthday, I had the opportunity to meet the Bavarian yodeling king Franzl Lang in person. I was very interested to learn the technique of yodeling from him. I then took the accordion and yodeled. The press was there and the next day there was a report: “A yodeling Japanese is looking for a dashing Bavarian girl”. That’s how I became a little famous. Through an acquaintance who was active in a music group, I had the opportunity to stand on stage and yodel at the carnival. The audience liked it so much that he told me: “You can join us tomorrow. You’ll get food and pocket money. So I stood on stage every day in lederhosen, with my snuff cloth in my pocket, and yodeled. That was the beginning of my yodeling career.

J-BIG: You actually just wanted to visit Europe?

Takeo Ischi: At the time, I was looking for a way to stay in Germany a little longer. I wanted to continue my mechanical engineering studies and work here, but I couldn’t get a work or study permit. So I got a residence permit for six months as a language student. During this time, I took a language course at the adult education centre and also took dance lessons. After six months, I had to leave the country. On my way back, I visited a friend in Zurich whom I had met in Japan at the yodeling club. Luckily for me, there was a big festival going on in Zurich at the time – it was called “Europe in Zurich”. There were big tents with bands playing. My friend said, “Takeo, you can yodel. Why don’t you go on stage?” So I yodeled, and in the evening I performed in a restaurant – and the audience was so enthusiastic that the boss of the restaurant offered me a room, food and pocket money to yodel there every day. So I was able to stay for a few weeks and save up for travel expenses. I had completely forgotten about my mechanical engineering studies by then. I thought to myself, “I can make a bit of money yodeling, so I’ll do that as long as I can”. Eventually, the media started to notice me and I had interviews on the radio and in newspapers. Two months later, I got an offer to appear on television. On a Saturday evening at prime time, I appeared live on Swiss television for a whole 13 minutes. It was a great success. A few days later, I got a call from a record company who wanted to sign me.

J-BIG: When was that?

Takeo Ischi: That was in 1974. I was 27 years old. A friend I met over lunch in Zurich helped me learn Swiss German and broker a contract with the record company Helvetia. So I was able to release my first two singles.

J-BIG: How successful were the records?

Takeo Ischi: It’s difficult to judge. The records were offered after my performances and sold well. But I never found out how many copies were sold at the stores. Nevertheless, I was very happy to see my record on display in a shop.

In order to get another residence permit, I went to an interpreting school for a year. During that time I had many gigs – but no fixed contract because I didn’t have a work permit. This meant that I received pocket money or reembursement for travel expenses for my performances. I was worried about what would happen to me in Switzerland after the year was over. It was unclear to me how to get a permanent job as a yodeler. The restaurant owner who had discovered me then helped me to get an official Swiss work permit – I didn’t even have to take an exam at that time. This meant that from May 1975 I was able to work officially and sign employment contracts. So from the moment I had an official work contract, I was a professional yodeler.

J-BIG: What kind of money did you make as a yodeler in the mid-1970s?

Takeo Ischi: In my early days, when I used to yodel on stage for fun at the carnival – three songs, ten minutes in total – I got 50 marks pocket money and free food. That covered my travel expenses and I was able to save a bit by performing every day for two weeks. In Zurich, I also got 50 francs per gig at the beginning, plus board and lodging. When I got my work permit, the fee was 200 francs at first. The amount rose steadily, and years later, I was paid 800 francs. When I signed a contract with a record label, the fee was 1000 francs per performance. On average I had maybe two or three gigs a month. There were months when I was booked more often, but also stretches without any gigs. I lived like this in Switzerland for six years.

J-BIG: What did your parents back home in Japan think about your professional yodeling career?

Takeo Ischi: My parents, especially my father, were very sceptical. To reassure them and make them believe that I would continue my studies, I sent them catalogues of machines and tools for a while. I also included newspaper articles about my achievements. This made it clear to my parents that I was successful with yodeling. With time, they realised that my yodeling career was something extraordinary. I was very happy that both my parents finally accepted my profession as a yodeler.

I had a Swiss girlfriend at the time, and we flew to Japan to introduce her to my family. They were reassured to know that I had a good life with work and friends in Switzerland. For me, Switzerland was the most beautiful country in the world – so why shouldn’t I stay? Studying mechanical engineering just completely slipped my mind.

J-BIG: So the fateful years for your career were 1973, 1974?

Takeo Ischi:: At the time, the years that followed and the decision to change careers did not seem so dramatic. But at the back of my mind was always the thought: “How long can I live like this? One day it will end, and then I will have to look for another job”. That’s how I felt in the late 1970s. Nevertheless, my fees kept rising – up to 1800 francs for a gig. In 1978, I produced my first record and cassette, “Der jodelnde Japaner” (The Yodeling Japanese), with the Eugster company. In 1979, I had the opportunity to perform in Japan for two weeks. A Japanese company with a branch in Switzerland wanted to tour Japan with a Swiss folk music group. I was hired to sing and yodel. The tour was a great success. Because I performed with real Swiss people, the Japanese audience perceived my yodeling as authentic. That’s how I became known in Japan. My record and cassette sold very well there.

Through an acquaintance who was a tour guide, my record came into the hands of Maria Hellwig. She was presenting three programmes on ZDF at the time, and in 1980 I was invited to take part in her programme “Früh übt sich”. Later I received a phone call telling me that the programme had been a great success. I stayed in touch with Maria Hellwig and she and her husband invited me on holidays several times. They asked me if I still had enough work in Switzerland. Switzerland is a small country and performance opportunities are limited. I had performed almost everywhere. That’s why Maria Hellwig’s husband applied for a work permit for me in Germany. In May 1981, I was able to get a visa with a work permit for Germany.

J-BIG: Where were you employed?

Takeo Ischi: At “Kuhstall”, the restaurant of the Hellwig family. I worked there as a permanent yodeler. I got a monthly salary and three meals a day. Sometimes I also helped at the bar and got to know the staff – including a nice cook who later became my girlfriend and wife. I also had regular appearances with Maria Hellwig on her TV shows, and she took me to gigs, like a radio station in Linz, Austria. There I met Karl Moik, who took me to the programme “Musikantenstadl”. As there were only three TV stations at that time, you quickly became famous by performing. In 1984, I went on my first tour of Germany. I worked for Maria Hellwig until 1988 and was able to go on different tours every year. That’s how I became well-known. As a yodeling Japanese, I attracted a lot of attention – but my name was difficult to remember. I tried to make the pronunciation of my name easier to understand. That’s why I write my name “Takeo Ischi” instead of the correct transcription “Takeo Ishii”.

I later quit my job with the Hellwigs’, started my own business and took an office in Bayreuth. By now I had gotten an unlimited residence and work permit.

J-BIG: The media landscape changed a lot in the 1990s. Private television revolutionised the television landscape. How did things progress for you during this time?

Takeo Ischi: This was generally a big problem for all artists who performed on television. Because the private stations added a lot more programmes, more artists were invited, even unknown ones, and the fees went down. I could barely cover my expenses. It was a bitter setback for us artists. Although my enthusiasm for the private stations was limited, turning down gigs was not an option. You don’t know when you’ll be invited back, so I accepted all the jobs, even if they paid less. You also earned less on the public channels. You used to get up to 2,000 marks for a song, and suddenly it was just expenses – maybe 500 marks for a longer performance. Then there was the change from DM to Euro. Everything suddenly felt twice as expensive, but it took a long time for wages to adjust. The financial crisis of 2008 brought another difficult period: there were fewer events, with even lower salaries. Fortunately, my office was able to find enough events for me during this time, so I was able to get through the crisis without any major setbacks.

Actually, I could have retired when I started my pension at 65. But at that time, I was still under contract with Rubin Records, the company that produced my CDs. The demand for gigs was still high, and I continued to enjoy performing.

J-BIG: Meanwhile you are a celebrity on the internet. Your songs, especially new songs, are viewed millions of times on YouTube. How did that come about?

Takeo Ischi: It wasn’t my idea at first. Someone else had uploaded my song “Bibi-Hendl” to YouTube. The video was accessed from all over the world in a short time. As a result, I became an insider tip internationally. That’s how the group The Gregory Brothers, which specialises in comedy music on YouTube, became aware of me. I already had a chicken in my hands in my music video “New Bibi-Hendl”. The Gregory Brothers made this motif the starting point of their song “Chicken Attack” with me. In the music video, I’m wearing lederhosen and holding a white chicken in my hand, which turns into a ninja. The number of views has risen rapidly – first one, then two, then ten million. By now, there are 25 million clicks. The video is also popular across Asia. In 2019, I was even hired by a Taiwanese heavy metal band for a live performance, where the song was covered in a metal version.

J-BIG: So you started an international internet career after you retired?

Takeo-Ischi: YouTube and the internet offer an extraordinary opportunity for promotion. If you search for Takeo Ischi, you will find many pictures and videos of events and performances. As a result, I have become better known to a younger audience in recent years. However, I have always been careful not to make everything from my private life public. That’s why I don’t have a Facebook account, for example. So fortunately, I can enjoy my retirement in peace. I get a small pension every month – if I had no other income, it wouldn’t be much. But luckily I bought a house and my children are already grown up and can support themselves. My wife still works and earns money, too, so I take care of the garden and household. That’s a lot of work: washing clothes, doing the dishes, ironing, cleaning the house and then cutting branches and sweeping in the garden. It keeps me busy every day. But sometimes I also have some quiet hours at home where I pursue my hobbies. I often watch YouTube, do art and crafts or play a musical instrument. And of course I also do voice training. There is a lot to do every day and I am not bored at all now that I’m retired. Every now and then I get a request for a performance or an interview, and so I continue to have the opportunity to travel to many countries. Now I’m not only known in Germany or Europe, but all over the world – thanks to YouTube.

In the meantime, I am one of the few still active professional yodelers. There are certainly still some who yodel part-time, but not full-time as a professional. After all, you have to be able to earn a living with your profession, pay taxes and contribute to the pension fund. To earn enough money, you need a lot of gigs – but that’s hard to do in this day and age. All the well-known professional yodelers have passed away and there is no upcoming generation to replace them. Interest in yodeling has declined and amateur yodeling is not enough for a career – you have to be masterful.

J-BIG: But you still perform and give concerts?

Takeo Ischi: There were fewer events lately because of Corona, but in principle I still perform. Last July, for example, I performed at the town festival in Zweibrücken and yodeled for an hour.

J-BIG: And you can still do that?

Takeo Ischi: I still manage, but have reduced the frequency of my performances. Being able to perform once a month makes me happy.

J-BIG: Germany and Japan have big cultural differences. You have managed to settle in here and build a successful, very “German” career. What were the decisive factors for your success abroad?

Takeo Ischi: In general, Japanese people are reserved. In Europe, on the other hand, people are comparatively open about their feelings. Body language plays an important role here and it is easier to speak one’s mind freely. In Japan, people are often unsure whether it is appropriate and whether their own opinion is even wanted. You can feel this reticence. It hinders personal development and a healthy relationship with your environment. Of course, friendliness is important. But it is also important to overcome your shyness and try new things. Learning a new language, for example: By learning not only German but also dialects, completely different opportunities and relationships opened up for me. That also applies to yodeling. You shouldn’t just play pretend. I learned real Swiss yodeling, real Bavarian yodeling and real Austrian yodeling – that’s how you become accepted everywhere and get closer to the local population. Adaptability is a significant factor. But it is just as important to communicate your opinion. Friendliness, tolerance, understanding – and being open to new perspectives – are central, so you don’t stand still and can develop as a person.