Josef Goehlen (91) is a former ZDF producer who brought cult anime series such as ‘Vicky the Viking’, ‘Maya the Bee’ and ‘Heidi’ to German television through German-Japanese co-productions and licensing deals with Japanese anime studios. He was a key figure in the first wave of anime in Germany. As such, he worked with Isao Takahata, one of the founders of Studio Ghibli, and the influential media makers Leo Kirch and Hans Andresen. Together, these television pioneers developed a business model for working with Japanese companies that was later adopted by other broadcasters. With great attention to detail and a flair for localising content, Goehlen was instrumental in adapting Japanese formats for German audiences and giving them their own unique touch, for example with German theme songs such as “In einem unbekannten Land…” (In an unknown land…). J-BIG talked to Josef Goehlen about the beginnings of German-Japanese co-productions in the 1970s.

J-BIG: Mr Goehlen, in the early 1970s, you were the first to bring anime to Germany on a large scale through co-productions between ZDF and Japanese studios. How did this come about and how did the first contacts with Japan develop?

Josef Goehlen: I started at WDR in 1960 and soon became an editor for children’s and women’s programmes. Three years later I moved to the smaller Hessischer Rundfunk in Frankfurt to work in the children’s programming department. There I first tried to get the Augsburger Puppenkiste, a German puppet show, a fixed annual slot in the ARD schedule. I succeeded, first with a Sunday morning slot and later for Sundays at noon during the Advent season. This was also thanks to the ‘Jim Knopf’ series, the great success of which had boosted the reputation of Puppenkiste within the ARD. Other Augsburger Puppenkiste productions followed, as well as news programmes and a live-action adaptation of Pippi Longstocking, which I produced in collaboration with Svensk Filmindustri.

My first contact with Japan came around the same time, in 1964. At the time, the Third Programme was introduced, which was supposed to have a distinctly educational focus. Low-cost productions were sought from all over the world to help achieve this goal. A trip to Japan, commissioned by the broadcaster, was intended to bring back licensed programmes suitable for adaptation by Hessischer Rundfunk. The trip was supposed to last ten days. It turned out to be 14 days, during which I found 1,000 minutes of programmes that, with some editing, could be of interest to German viewers.

Free Subscription

“J-BIG – Japan Business in Germany” is the e-mail magazine dedicated to Japanese companies and their business activities in the German market.

This material was first shown to me on 16mm prints in my hotel room in Tokyo by a 19-year-old student called Tomosuke Suzuki. Suzuki later became a co-producer of my animated series such as ‘Vicky the Viking’ and ‘Maya the Bee’. I still talk to him occasionally.

J-BIG: What happened to the material from Tokyo?

Josef Goehlen: When the material arrived at the Hessischer Rundfunk weeks later, our concept for the Third Programme had already changed considerably. There was less demand for scientific and educational programmes and the contributions from Japan had to be edited from a different perspective than planned. So I invented new formats and used the Japanese material, among other things, for the magazine series ‘Ich wünsch mir was’ (I make a wish) with Kater Mikesch and Hilde Nocker. It took a lot of imagination to turn the acquired material into programmes suitable for German television.

My trip to Japan almost 60 years ago was the catalyst for my love of Japan and my respect for the anime treasures that the Japanese television industry had in abundance. On my very first visit to Tokyo in 1964, I met Hans Andresen, a friend of Leo Kirch and co-founder of a joint company in Munich. The two of them had developed a very lucrative business model for buying and selling film licensing rights. I remember Hans Andresen as a witty, educated world traveller who thought cynically – and sometimes acted cynically, as well – spoke six languages, was always on the lookout for new business and intellectual adventures. No one knew exactly where in the world he was at any given moment, and he conducted his contract business from his hotel room or from public telephones. His office was in a suitcase. Hans Andresen was a lonely single man, yet a genius of human empathy, who loved art and science, collected books on Greece, the Roman Empire and Egypt, and bequeathed his large collection of paintings by successors of the classical Dutch painters to the University of Santa Barbara. He was a witty eccentric who planned and curated his travels on emotional rather than logical considerations, but then clearly and calmly stated his demands in negotiations. I could witness with admiration his negotiations with Disney in LA or with Zuiyo Enterprises, the forerunner of Nippon Animation, in Tokyo.

With him, we devised a co-production model that required each co-production partner to make a financial investment commensurate with the amount of rights acquired, depending on the nature and scope of the rights. The production was based in Japan, the writers were based in LA and Munich and the editing was done in Mainz at ZDF, in Munich at Taurus Film and in Vienna at ORF and Apollo Film. Distribution rights for Asia were held in Japan by Nippon Animation and for Western Europe, the Anglo-Saxon world, Africa and South America by Beta Film Munich. This model, which may sound a little complicated, made production inexpensive for each partner, increased production quality and at the same time secured ZDF’s editorial sovereignty. This model was used to produce 78 episodes of ‘Vicky the Viking’, and later 104 episodes of ‘Maya the Bee’, 52 parts of ‘Pinocchio’ and 52 episodes of ‘Alice in Wonderland’.

J-BIG: Was it difficult to set up such a model with Japanese companies?

Josef Goehlen: It was not easy, but these co-productions were facilitated by the fact that Japanese companies at that time wanted to enter the European market and were therefore open to European content. They had done enough for American companies, and now they wanted to work directly with European companies, especially those that dominated the German television market. The door to Europe, according to the Japanese partners, was to be ‘Heidi’. The Japanese had contacted Beta Film during my active time at Taurus Film between 1970 and 1973 and had their research in ‘Heidiland’ in Switzerland and Frankfurt supervised by us. I met Isao Takahata, the future co-founder of Studio Ghibli and director of ‘Heidi’, during the trip or shortly afterwards in Japan, and although our English was not very good, we were able to communicate with each other in a way that was fruitful for occasional editorial criticism and further collaboration.

J-BIG: So you worked more and more closely with Japan. What was this experience like for you in the 1970s?

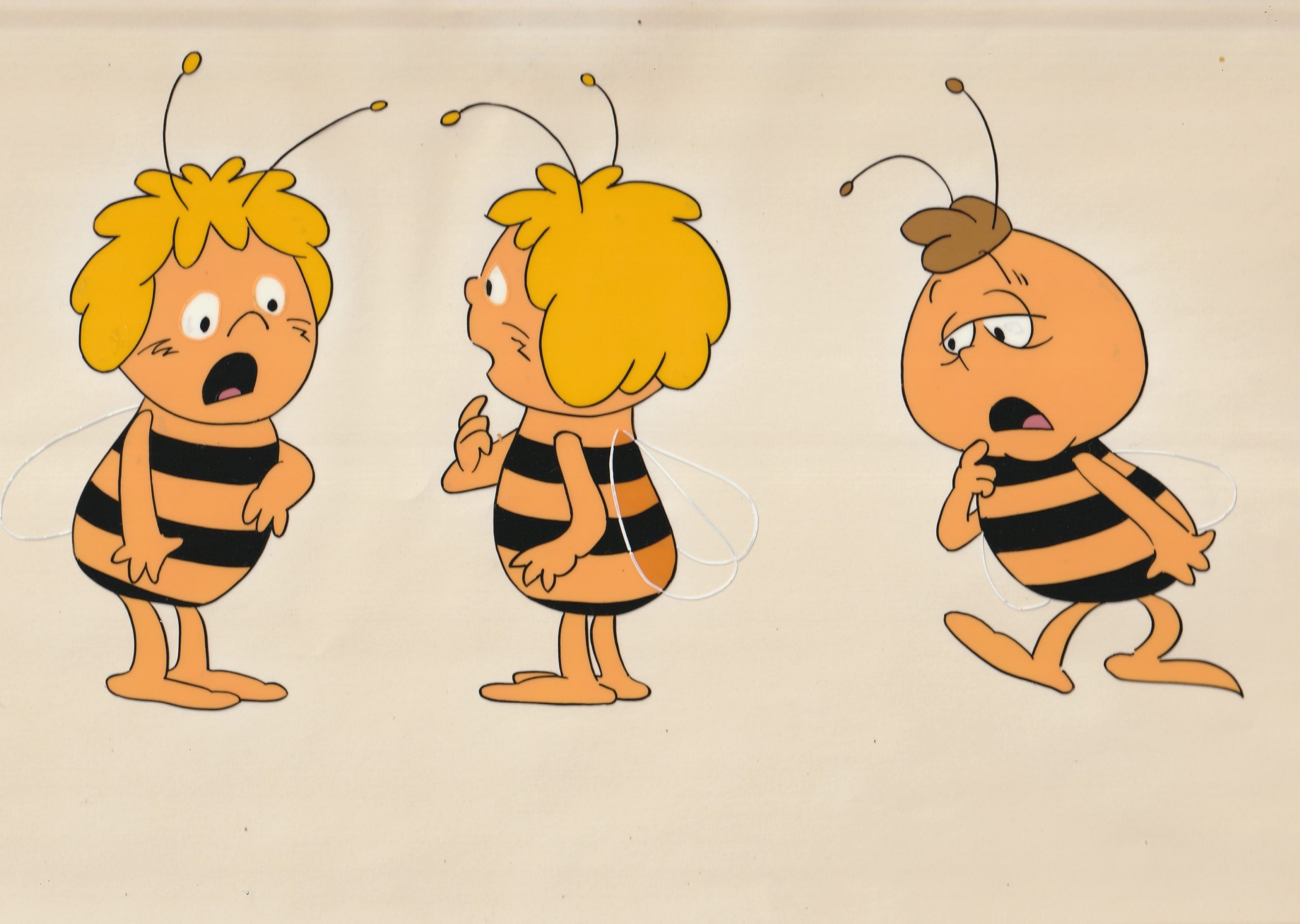

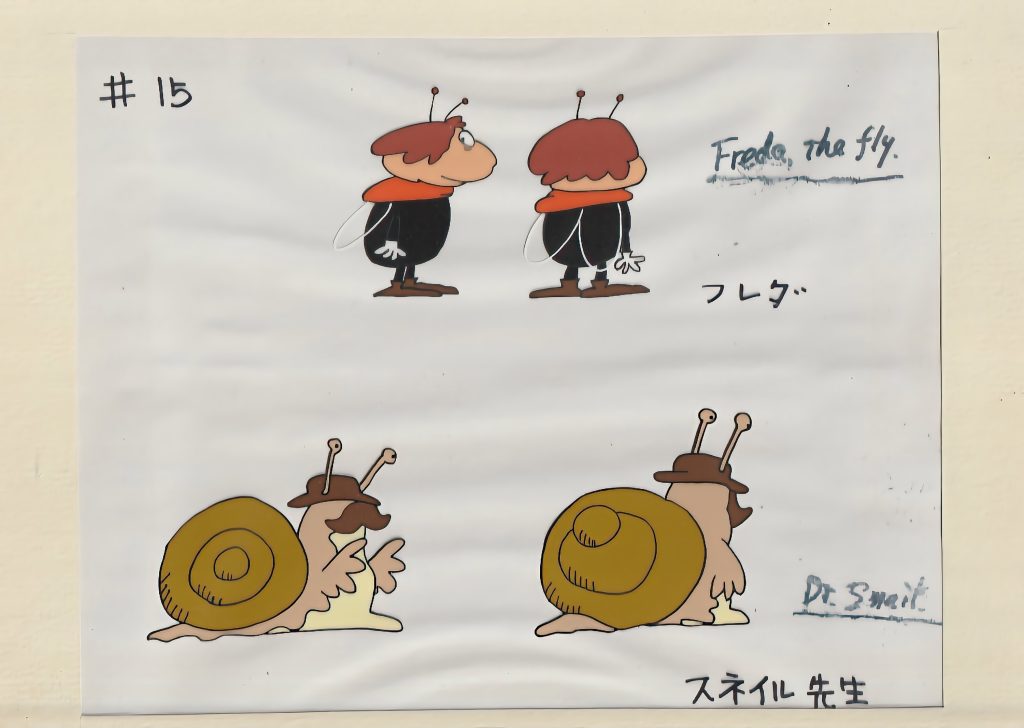

Josef Goehlen: The repeated stays in Tokyo were exhausting, but also stimulating and physically and mentally enriching. I enjoyed the Japanese baths, which were refreshing not only because of the different pools of water at different temperatures, but also because of the green tea served afterwards. I enjoyed the visits to classical concerts in huge music halls, the theatre performances of Kabuki and No drama, which are difficult for a European to understand, the walks in Japanese parks, monasteries and Buddhist temples designed according to mediative concepts, but also the introduction to digital processes for anime in the development departments of anime studios. These techniques were still in their rudimentary beginnings, but they were oriented towards the future. The work on ‘Vicky the Viking’, ‘Maya the Bee’ and the other animated series, on the other hand, was still carried out by a large number of sketch artists designing countless slides in labyrinthine rooms.

Communication with the Japanese animators was not easy. The meetings were exhausting when it came to my requests for changes. Communication was difficult not only because of the need for interpreters – Hans Andresen and Tomosuke Suzuki did their best – but also because of the partners’ proud self-image. “Someone from the West is coming to teach us something,” they may have thought. That hurt the pride of the creative people. In the beginning, long discussions were the only way to get things done; later, once trust had been established, short remarks were all that was needed to implement changes that had to be presented editorially. In the end, the working model of editors in Mainz, Vienna and Munich, writers in Los Angeles and Munich and production in Tokyo prevailed, so that ARD was able to follow the ZDF model for the ‘Nils Holgersson’ series.

J-BIG: Although it was probably not clear from the start that it would become such a successful model.

Josef Goehlen: The realisation of ‘Vicky the Viking’ was supposed to be the general test. It could not be ‘Heidi’, because production had already started and our influence was only that of the licensee. So ‘Vicky the Viking’ was the key project for our entry into the co-production business. It had its beginnings in the mid-60s.

The story of the little Viking boy was translated from Swedish into German in 1964, won the German Youth Book Prize in 1965 and landed on my desk at the Hessischer Rundfunk via a representative of the then still existing Herold publishing house. The publisher expected the material to be made into a TV puppet show by the Augsburger Puppenkiste. But I was able to persuade the publisher to wait until I saw a financial opportunity to bring the story to television.

I only saw this opportunity when I became involved with Beta Film and Taurus Film in 1970. Here people expected new ideas that could be offered to the broadcasters, such as WDR. Leo Kirch had been persuaded to take the German-Czechoslovakian series ‘Pan Tau’, co-produced by WDR, into world distribution. However, sales proved difficult, so WDR was offered the opportunity to co-produce ‘Vicky’ as an equal countermove. WDR accepted but demanded editorial control and sent specialists from East Germany and Czechoslovakia to set up a studio in Upper Bavaria. The first takes were to be approved by a certain date, but the deadline came and went with no film to be seen. There was a large model of a ship and two characters, nothing more. The work was terminated and as there were further disputes because of the slow sales of ‘Pan Tau’, the ‘Vicky’ contract was cancelled. Now I had the ‘Vicky’ material back in my drawer, this time at Beta Film. What to do now?

Hans Andresen had to help – and he did so by bringing Japanese partners on board. Tomosuke Suzuki did the same at Fuji TV and I talked to ORF and ZDF. I persuaded my friend Alois Schardt, who had just taken over the children’s programme at ZDF, to go to Tokyo, where he could see for himself how design was converging with Western tastes. The basic funding for the co-production model was provided by Leo Kirch and his Beta Film distribution company, even before a contract was signed with a broadcaster. The co-production model proved its worth, and after ‘Vicky the Viking’, other productions were made, as already mentioned.

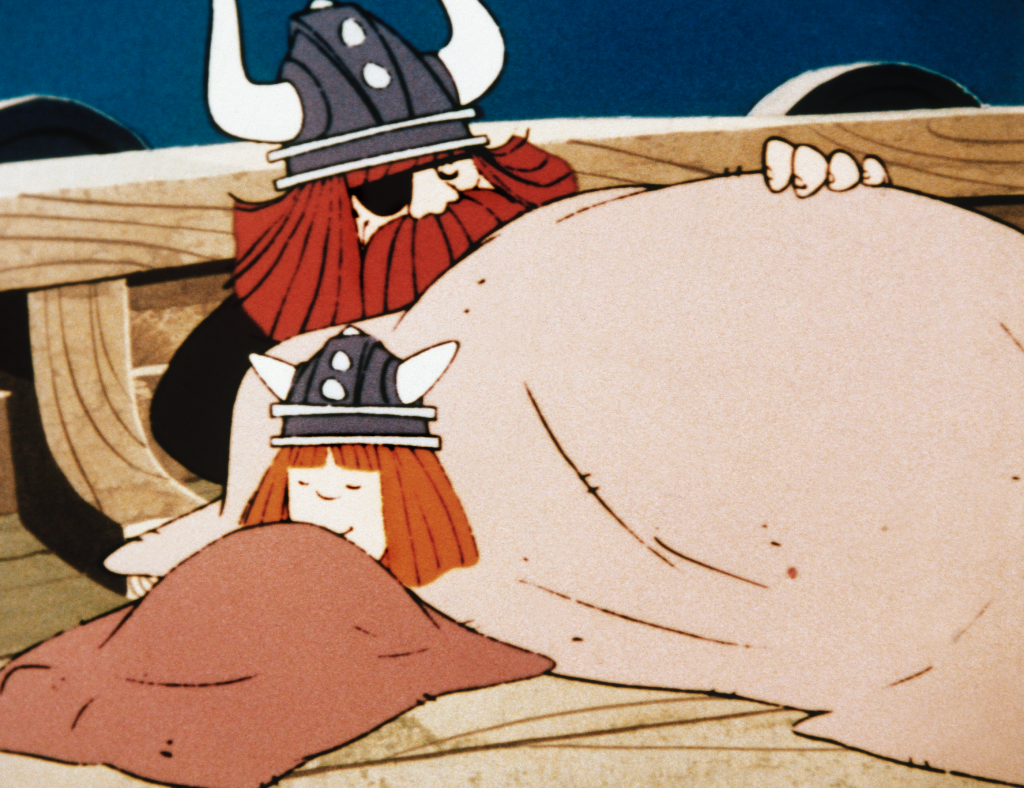

J-BIG: ‘Vicky’ was first broadcast in 1974. How was the series received by ZDF and the public? Was it an immediate success, making ‘Maya the Bee’ a logical consequence?

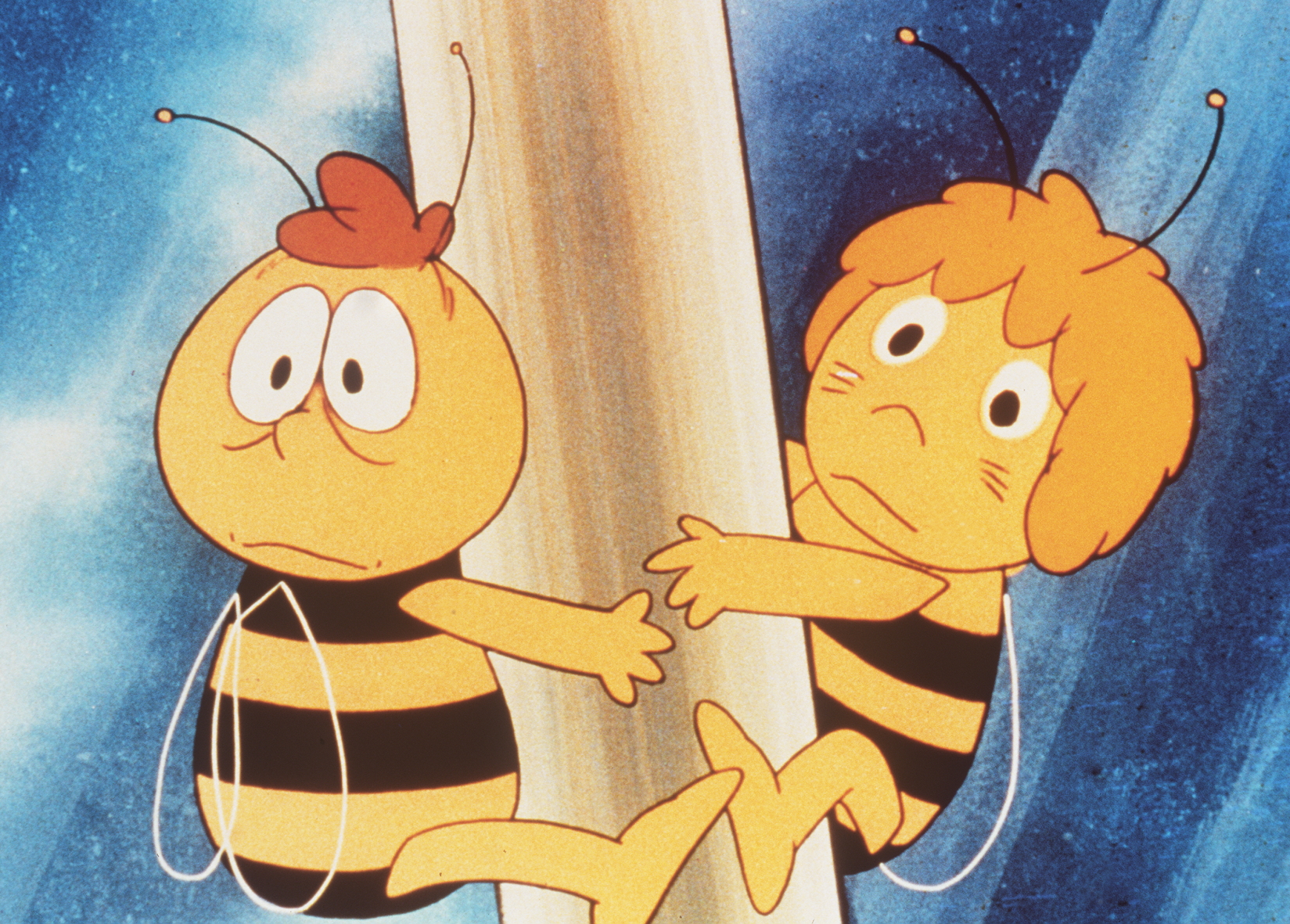

Josef Goehlen: ‘Vicky the Viking’ was a huge, overwhelming success that not even those at ZDF who wanted the programming to be more educational could deny. What they overlooked was that ‘Vicky’ is, in a poetic and humorous way, a prototype for the emancipation of a child in an adult society and can therefore serve as an archetype. A boy who fearfully but courageously stands up to adults. The popularity of the series showed in the way people imitated Vicky’s gestures, such as the rubbing of the nose I invented when he had an idea, the familiarity of the title song by Christian Bruhn, sung by the Bläck Föös, and the programme music by the equally talented composer Karel Svoboda. The almost uninterrupted presence of the series on television screens, its cinema presence in the form of Michael “Bully” Herbig’s feature film, the change in rights holders and the remake of the series are still proof of its success today. The same can be said of Maya the Bee. Both series have triggered an almost excessive boom in merchandising, which, to the extent that it is today, was never the aim of the creators, including myself. We simply wanted to entertain children and their families in a meaningful and tasteful way. Both titles took on a commercial life of their own. The Japanese showed us the way: Even before ‘Maya’ was broadcast in Europe, it had been shown in China. The series was made available to Chinese television with advertisements from the Japanese photo industry. Although no Chinese could buy a camera at the time, they advertised it anyway, with the intention, as they told me, that “in 50 years, they will be able to buy one”. How right they were!

Both ‘Vicky’ and ‘Maya’ have become cult series and brands that can be and are used all over the world. But I am grateful to all those who love the original German-Japanese version more than the newer computer-animated version, because they feel that the original version was created with love and commitment to the programme, poetry and humour.

Of course, the success of the children’s programme was not overlooked by ZDF. It couldn’t be, because it was just too big. Nevertheless, there were always questions from individual, persistently pedagogical members of the board about the sense and purpose of such programmes. The latent conflict was resolved when, after the broadcast of ‘Captain Future’ on ZDF, I moved from the children’s programming to a newly established main editorial department called ‘Serials and Early Evening”‘ My successors in the children’s department adjusted their programme direction to be more explicitly pedagogical.

J-BIG: Speaking of ‘Captain Future’: This was one of the licensed series that followed ‘Heidi’. In addition to German-Japanese co-productions, licensed Japanese series were the second line of anime formats on ZDF. How did the licensing come about?

Josef Goehlen: Beta Film in Munich was the only German company at the time that had contacts with producers in the USA and an overview of what was happening in TV in the USA and Japan – thanks to open-minded, entrepreneurial people like the aforementioned Hans Andresen and his comrade-in-arms in the USA, Klaus Hallig. The first Japanese anime series, such as Anne of Green Gables and Captain Future, were offered in American versions through the US channels. We adapted them for German and Austrian television.

It was only when we took over ‘Heidi’ as part of our co-production model that it became possible to acquire licensed programmes directly from Japanese companies. With our dubbing, we were able to adjust some of the dramaturgy to make it more comprehensible to our audience. Cuts and changes were made according to contractual agreements. However, the basic message and design remained the same. Most of the music was also changed to suit German tastes, and some theme songs are still popular today, e.g. “Heidi, Heidi, deine Welt sind die Berge….” composed by Christian Bruhn and sung by Erika and Gitte, “Hey, hey, Wickie” sung by the Stowaways, later the Bläck Föös, or the ‘Maya’ song “In einem unbekannten Land…” composed by Karel Svoboda and sung by Karel Gott. The German instrumental theme song to ‘Captain Future’, composed by Christian Bruhn, is still popular and well-known today. Along with ‘Heidi’, it was the most successful licensed Japanese series, and it was common for schoolchildren to exchange photos of scenes in the school playground.

J-BIG: ‘Captain Future’ certainly caused a lot of discussion, as did the experiment with ‘Speed Racer’ in the early 70s. Too “stupid and violent” and “parental protests” read some of the headlines at the time. What were the reactions really like?

Josef Goehlen: There are many manga and anime artists in Japan who draw their mangas, write the texts and design their animation videos in a poetic, classical, traditional graphic style. These artists, however, do not find their way into the mass media, but are reserved for special exhibitions. The criticism of the series produced for the mass media was not so much about the content, but more about the design, which had a sci-fi, magical-technical look – with distorted figures with swollen heads, big eyes and big mouths, in keeping with the Japanese anime style. I could understand some of the criticism. After all, most of the series were as “loud” as the volume in Tokyo’s pachinko halls. The discussion centred around an aesthetic that was unfamiliar in the West. In the case of Captain Future, the design had already been toned down because the illustrators had taken their cue from the 1940 American print editions of the captain making peace in space.

Criticism of the ZDF broadcast related to both the unfamiliar design and the way crime was fought in space. The show was broadcast in the early 1980s, a time when artificial intelligence was still a foreign concept. Some of the board members were not yet ready to tolerate a fairy-tale futuristic story with unusual characters. I myself took a lesson from this and paid particular attention to the graphics in the co-productions, so that they didn’t drift completely into a Japanese-modernist fantasy world. In this way, the German-Japanese-American cooperation proved its worth in the co-productions.

J-BIG: After you were no longer responsible for the children’s programme at ZDF, did you continue to pursue the subject of anime – especially the developments in German private television in the 1990s?

Josef Goehlen: After I gave up responsibility for children’s programmes at ZDF, I didn’t really pursue anime programmes anymore. I was responsible for the early evening programme, which was mostly made up of German commissioned productions. I myself took over ‘Alf’ and ‘The Simpsons’ as licences. ‘Alf’ was a success, ‘The Simpsons’ less so at first. They only became bestsellers on Pro7 because the broadcasting environment was more interesting for young viewers. My successors in children’s programming then licensed the Japanese series ‘Sailor Moon’, which was cancelled after only a few episodes and only later found its place on RTL2. I think that the viewers at that time subconsciously realised at the first attempt that this series, which was produced according to the pure laws of manga and anime, didn’t come into the programme with much love and commitment, as it also didn’t have particularly good dubbing.

J-BIG: How do you feel about today’s children’s programmes and the remakes of your 70s series?

Josef Goehlen: A 3D version allows a new dramaturgy analogous to computer games, and this seems to have created new viewing habits. You propagate as modern what you created as a media designer to serve up a fast-paced, action-packed story. The story must be loud and colourful. Some programme-makers think this is how viewers want to be entertained. But they overlook the fact that this is what they themselves prefer. What is considered modern is fashionable and not necessarily of high quality. The new look of my works ‘Vicky’, ‘Maya’ and ‘Heidi’, which were produced with great dedication in cooperation with Japanese artists, has also suffered from this. In addition, the poetry and the more sensitive humour, which the drawn anime characters allowed more than the computer-generated ones, have been completely forgotten. I don’t know what links still exist with TV producers in Japan. But I still have a dream of creating a series that allows the return of traditional pen and ink drawing.